Is Casio the least sexy watch company in the world? It’s a rhetorical question, of course. You don’t get weaponized in a Shakira diss track by accident. Casio makes calculator watches and straight-up calculators. The company’s actual name is Casio Computer Co., Ltd. Computer. Get thee behind me, Satan.

And yet. Who’s cooler than Satan? Again, rhetorical.

Born from Ashes

While Seiko and Citizen, the other two big Japanese watchmakers, trace their horological roots back to ye olden mechanical tymes, Casio has a different origin story. In 1946, Tadao Kashio founded a company that made a roach clip you could wear like a ring. It was actually his brother’s idea, but the company that would come to be called Casio (Kashio, Casio, get it?) was and is a family business — the current CEO is Tadao’s nephew.

A TB infection had spared Tadao from the Emperor’s army (reportedly to his shame) so as Japan got down to the bloody business of building its Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere he instead set up a lathe in his backyard and made aircraft parts. That backyard happened to be in Tokyo, and General LeMay’s fearsomely efficient fire bombing eventually put an end to his grassroots patriotism, the Sphere, and most of Japan’s major population centers. But that was the past in 1946. In the present, with the heart note of napalm still in the air, tobacco was in high demand and short supply, and rebuilding from scratch was busy work. With the Casio roach clip you could smoke that butt to ash while keeping your hands free for reconstruction/survival. Roach clip money funded Casio’s lateral move into electronic calculating machines, which grew into a prowess with integrated circuits that eventually made the production of quartz watches a no-brainer.

Allegedly a photo of the OG Kashio Yubiwa Pipe, uncredited and stolen from a Reddit thread.

The quartz crisis is usually framed as a story of legacy watchmakers that adapted or didn’t, but it’s interesting that quartz came from within the established watch industry. A consortium of Swiss companies were scrambling to develop a viable quartz movement, but Seiko, the most ambitious of the Japanese watchmakers, beat them to market. All of these players seem to have seen quartz as a route to superlative timekeeping and expected to charge a fat-margin premium for it. Seiko’s Astron, the first commercially-available quartz watch, cost 450,000 Japanese yen in 1969, or about $12,000 when adjusted for inflation. It’s common to say that it cost “as much as a compact car,” but it’s more interesting to compare it to a Rolex Submariner, which apparently went for around $175 at the same time: that’s just $1,500 with inflation. I guess watches were cheaper back then. Now the world is full of watches that cost as much as a small plane, and a few that cost as much as a big one. Quartz watches don’t generally command plane money, but an F.P. Journe Elegante will still set you back fifty grand, which will also buy a nice foreclosed three bed/two bathroom home in Ohio.

What’s never been clear to me is if everyone or anyone at the time saw where the quartz road led. Watch people today tend to view the quartz crisis as a dark age that descended on watchmaking, wiping out a century of fine mechanical artistry in favor of cheap disposable tat. It’s hard to imagine that the companies charging so eagerly into the breach had that destination in mind. Was it obvious that solid-state technology scales in a way that makes that inevitable? Maybe only in retrospect. I can’t believe the Swiss saw that as the endgame, or they would have locked their electrical engineers away in the country’s warren of underground bunkers. But it was only the dawn of the silicon age, and the hard light of high noon was yet to shine.

Anyway, Casio’s watch business was born in the maelstrom of the quartz crisis. The company pivoted, not from mechanical watches, but from calculators. This might explain why it’s not quite like any other watchmaker. Five years after Seiko’s Astron, Casio launched its first watch, the Casiotron. It went for a lot less than the Astron, though it was still expensive for the time, around $1,000 adjusted for inflation. But the economics of silicon meant prices kept falling. I haven’t managed to track down the moment when quartz flipped from premium to cheap-as-chips, but by 1978 the Casio F-100C, a pretty basic LCD quartz watch, went for $39.95, less than $200 inflation adjusted, and just two years later the similarly-spec-ed F-7 retailed for $19.95, under $75 today. At that point, you probably felt kind of silly if you’d bought a Casiotron six years earlier.

#1 Best Seller in Men’s Wrist Watches, apparently. Still.

By 1989 Casio was able to introduce the F-91W, a watch that remains in production today and is probably the best-selling timepiece of all time. You can get one right now for fifteen bucks. It’s the democratic promise of quartz in its purest form: a watch that’s dirt cheap, keeps accurate time for years without fuss, and is hard to kill. Its durable, no-bullshit essence has made it a favorite of terrorists and presidents and countless millions of people all around the globe who just want to know what time it is.

Big in Japan

Casio’s great success is its G-Shock line, playfully ugly and indestructible watches that lean into their quartz-ness with lots of LCD action and crazy features. You can buy a G-Shock for less than 50 bucks if you just want to play hockey with your watch as the puck, while the top-end limited edition models now command prices north of $8,000.

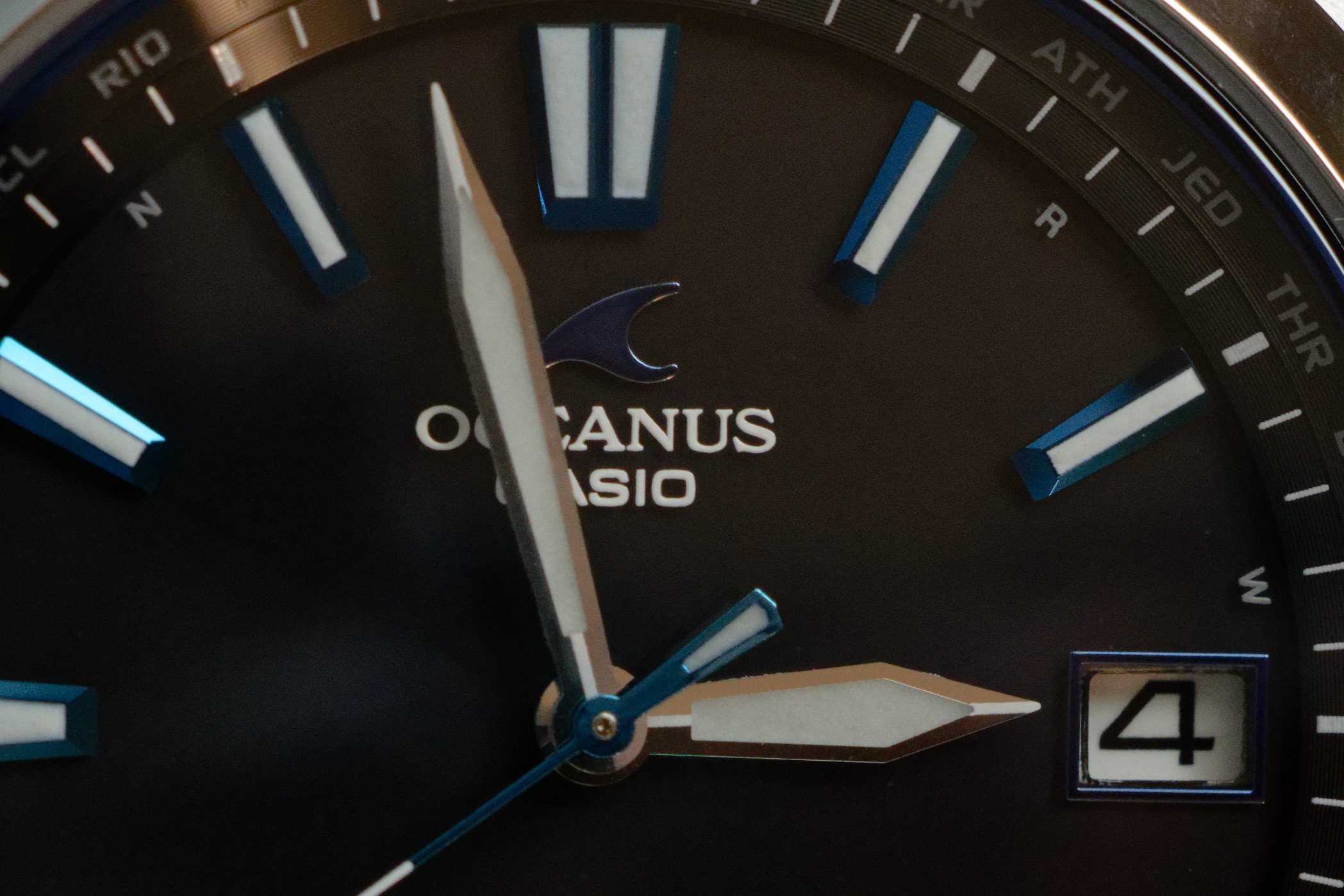

But I’m more of an analog guy, so today we’ll consider the Casio Oceanus S100, a simple three-hander introduced over a decade ago. Impressively it’s still a current model, though I doubt it will have a run as long as the F-91W. It’s way more expensive than that watch, but not really any sexier. And yet it has its charms, and possesses a kind of practical romance that appeals to me.

The Oceanus line today is mostly Japan-only, though it was exported for a while years ago. I guess the idea of a premium, sporty, tough but also dressy watch with diver influences didn’t catch on abroad.

You have to assume that Casio didn’t worry much about how Oceanus branding would play beyond the home market.

The S100 is the smallest of the current lot, 40mm across ex-crown, and all it does is tell you when now is, which is my thing. Its specs are hardly unusual: radio synchronization, solar charging, perpetual calendar. This was all bleeding edge at the end of the 20th century, but now it's bog-standard stuff that you can find in plenty of watches retailing for under a hunge from any of the big Japanese manufactures. But this review posits that maybe, in this era of ubiquitous internet and mechanical watch fetishism, maybe we have become blind to the essential romance of something like the S100.

What Is this Thing?

I suspect that when Casio made the S100, the target buyer was a Japanese businessman who wanted a nice, accurate watch that he wouldn’t have to fuss with, that suggested the possibility of adventure the way a Lexus SUV invites a fantasy of driving off road, and that looked like quality while not running the risk of being fancier than his boss’s watch. I suspect that the men who bought it for those reasons were not disappointed.

But the S100 also appears to have found a niche farther afield, as a no-maintenance beater for watch enthusiasts who sometimes want a break from the delicate exigencies of their mechanical timepieces. This is the sense I get from the fairly numerous English-language user reports that have popped up over the last decade. The S100 has just enough to make it interesting for a watch snob: it’s built to an unusually high standard for its price by a company that’s often overlooked in horological circles. The fact that it keeps perfect time for years and years with no intervention also makes it appealing to people who want to be able to slap it on after long periods of neglect, and stands in sharp contrast to the Tamagotchi demands of mechanical watches.

Style-wise, the S100 is a mongrel. Imagine a Grand Seiko had a baby with a diver that had cross-over field watch ambitions and you might picture something like the S100. The beveled, high-polish applied indices would suggest the boardroom if they weren’t bright blue on four sides and topped with lume. Further offsetting the dressiness are crown guards, balanced by a purely ornamental protrusion on the left side of the case, that imply the watch is meant to deal with physical activity. The Oceanus logo and the “TOUGH MVT” text on the dial are more PTO than CEO. The watch is allegedly watertight to 10 bar, but the lack of a screw-down crown and the big pusher next to it suggest that this is a somewhat theoretical rating. Despite the ocean theme and pressure rating, there’s no rotating bezel: clearly you’re not meant to wear this with a scuba tank.

Which is fine by me. I wanted a watch that could be dunked with impunity, but I generally don’t put my head underwater on purpose. I’m more concerned about jumping into the pool to save a flailing kid. As far as salt water goes, I’m no Cousteau but I might need to grab someone who’s stumbled into the surf when they were supposed to be skipping rocks. I like the opportunities for fine workmanship that a watch with some ornament affords, but I also like to imagine that I might have adventures out in the world. Guard that crown, baby.

First Impressions

Despite recent baby steps towards a more international presence, the Oceanus line remains largely Japan-only, so if you want a new S100 you’re looking at one of the specialty Japanese exporters or eBay. I bought mine new from an eBay seller, who included an origami crane in the box. At first I thought this was cool, but then I realized that you can probably buy origami cranes in bulk from China, and I felt a little sad. I kept the crane anyway, since it’s the thought that counts, and maybe I was being too cynical.

When I opened the watch box, I saw the S100’s hands snap from 12:00:00 to the current time in Tokyo. This is one of the S100’s tricks (presumably shared with all of Casio’s solar watches): if kept in the dark for a week, the hands park at 12 and the watch dozes quietly. What dreams flit through the simple matrix of its mind? It can supposedly hibernate in darkness like this without loosing track of time for up to three years. This function appeals to me: it’s like the watch is a flower at night, furling its petals until the dawn, even if that dawn might be years in breaking.

With the hands having resumed their march, I considered my new watch. I decided I… liked it? I wasn’t sure. Watches, more than most consumer goods, don’t look much like the pictures you see of them when you’re shopping online. Partly it’s a question of magnification, and partly it’s the light — watches are often designed to play tricks with light and static images rarely tell the whole story. This is definitely the case with the S100, which is surprisingly flashy in person. Literally so: it has lots of high-polish facets that catch the light and glint brightly as the watch moves.

I’ll drop this lume shot here because I need something to break up the text. The lume seems good to me, though I’m not an expert. The hands remain visible all night if you charge them with a flashlight at bedtime.

This is most noticeable with the applied indices, which also happen to be an intense blue on four sides, so you get a light show of bright blue flashes as the watch moves. I knew blue was a signature color used throughout the Oceanus line, but I expected something more like heat blued steel. This is not that. The S100’s blue is really electric, I assume some kind of PVD coating. I wasn’t sure how much I liked it.

The blue is in your face, but the potentially busy text on the chapter ring is not. The 29 cities represented by three-letter codes barely make themselves known, thanks to the tiny size of the printing and fact that the chapter ring slants down towards the dial. I like how these codes reference the geographic world, tying the watch to a specific moment in history when those cities not only existed but were significant enough to stand in for a whole time zone. I could decrypt about half of them. Maybe one day I’ll look up the rest, or just let the mystery lie. The other indicators scattered around the dial that allow you to configure various functions (daylight savings, radio functioning) are also more discrete than you might imagine if you’ve been looking at magnified images of the watch on your screen.

Case Logic

The S100 case and its integrated bracelet are made of titanium. Titanium is indelibly linked in my mind with military aviation, especially the swing-wing structure of the Grumman F-14 and damn near the whole of the Lockheed SR-71. The F-14 was the basis for the aircraft in a cartoon I watched as a child with fundamentalist intensity. It was also imaginarily flown by Tom Cruise in the popular film/recruitment tool Top Gun, and when I saw it at as a boy it defined what I thought was cool for quite a while. I worry that Top Gun does not survive adult scrutiny, but the SR-71 Blackbird remains immune to revisionism in my heart, so it’s fun to have a titanium watch.

The case finishing strikes me as very good, though I have to admit I’m not as much a connoisseur of this particular area as I am of dials, which readily reveal their features and faults to any attentive eye (more on the S100’s dial later). You get a mix of fine brushing on most surfaces, set against a high-polish bezel the flows nicely into the domed crystal. The afore mentioned crown guards and left-side protrusion are actually quite complex in form, and also have mirror polish on the top surface. It all creates a muscular display of technical precision.

If you poke around the few English-language forums that discuss Oceanus watches, you’ll likely come across the notion that Oceanus cases are made in the same place as Seiko’s hallowed Grand Seiko cases. I initially assumed this was wishful thinking, but drilling down, it seems more likely than not to be true. Hayashi Seiki Seizo has been making watchcases in Japan since 1921, and the company is nothing if not close to Seiko: when the earthquake that set off the infamous tsunami of 2011 nearly knocked down the Hayashi factory building in Fukushima, employees scrambled into the wreckage to salvage Grand Seiko cases that were in production. Within a few weeks, critical machinery had been extracted from the unstable building and set up again in Seiko’s own Shizukuishi factory. Among that tooling would have been the polishing machines used to create the famous sallaz mirror finish on Grand Seikos, a feature that Casio also touts for the S100, albeit without Seiko’s panache for creating an air of exclusivity. And if you go to the “Watchcase and Precision Parts” section of Hayashi’s utilitarian website, you’ll see an image of their factory floor with a Grand Seiko poster on the wall, and a little further down the page, a close-up of a clearly marked Oceanus case back. (Hayashi also does ion coatings, and I wonder if they’re responsible for the bright blue on this watch.)

An Oceanus case back on the Hayashi site. QED.

Since we’re talking about factories, I’ll mention that the S100 is made on a special line in Casio’s Yamagata factory dedicated to Oceanus watches and the highest-end G-Shock models. There are videos of it online: workers kitted out in white clean suits operating very fancy looking equipment, with lots of extremely close-up views of watches on video monitors. In general you have to pay a lot for a watch before you can say with any certainty who really designed it, where its parts come from, and who assembled them into a working timepiece. The S100 offers an unusual amount of transparency for its price.

Crown Click

You might have thought that because this was a quartz watch you would be spared my usual rumination on knob feel. Silly rabbit! Let’s start with the crown, which is the main attraction. Turning it in the pushed-in position (as you would normally wind a mechanical watch) does nothing, but I’m a completist so we’ll start there. Oddly, considering there’s no point in doing it, turning the crown here is quite satisfying. You don’t get the meaty resistance of keyless works tensioning a mainspring, but the movement is nicely damped.

Pulling out the crown one click feels fine — it’s neither too hard nor too easy. Then the real fun starts. When the crown pops out the seconds hand snaps to point towards the current time zone, indicated by three letter codes printed on the chapter ring (don’t worry, the watch is still keeping time). Turning the crown in either direction advances the pointer around the dial, with distinct clicks. The force required to turn the crown, while never excessive, rises as you approach the click point, then suddenly drops as you turn through the click. There’s more dynamism than, say, changing the date on an ETA 2824 (pleasant in its own way). It’s a very satisfying feeling, and not something I expected to find on a quartz watch.

The. S100’s crown, a surprisingly rich tactile experience.

Changing timezones causes the hour hand to swing delightfully to the new time in a way that feels very alien if you’re accustomed to mechanical watches, which generally advance their hands in a staid and utterly predictable manner. Click forward through time zones and the hour hand sprints smartly ahead. Click backwards and the hour hand reverses, a little slower though still spritely. Endearingly, it overshoots the target hour and then advances to the precise position, presumably some kind of alignment check.

Speaking of alignment, like all of Casio’s “Tough Movement” analog watches, the S100 checks the position of its hands once per hour to make sure they’re where they’re supposed to be. It does this by shining a light through tiny 300-micron-diameter holes in three gears driving the hour, minute and second hand. At the appointed moment (five minutes to the hour) all three holes should line up and the light can shine all the way through. If it doesn’t, the watch knows there’s a problem and gets to fixing it.

Casio marketing suggests this is to ensure proper hand alignment if some violent shock knocks things out of whack, but I think that might just be a way to make hay out of a technical feature that’s otherwise boring: namely, a system that lets the watch sense hand position so it can match the displayed time with its internal clock. It seems to me that an impact hard enough to make a gear slip would be more likely to knock a hand out of true on its stem, and this system wouldn’t address that (since what it really knows is the position of the underlying wheel, not where the hand is). But anyway, I like the idea of a light shining through tiny holes inside my watch.

Dialing Down

My unease about the S100’s looks faded with familiarity, and I came to enjoy the blue sparkle of the indices and the chapter ring trim. You can see the pizza-slice seams between the six solar cells that are hidden below the semi-translucent dial; I think the actual dial surface is smooth, but the texture of the solar cells comes through visually and gives the dial a matte, understated look.

I cannot deny the appeal of the seconds hand, which hits its marks all the way around: any doubt could as easily be parallax error as misalignment. People accustomed to the sweeping second hand of mechanical movements might not realize that a shocking number of quartz watches have second hands that never actually point at the second marks. Some are consistently offset by a given amount, while others hit their marks for one section of the dial but miss on another. I’ve even read claims from watch makers that misaligned second hands are either an engineering necessity (Timex) or badges of handmade honor (Vaer). I think it just costs a little more to do it right, and watchmakers know from experience that most quartz buyers don’t care enough to justify the production expense. But I care. The Oceanus line, like Grand Seiko, has a good reputation for honoring the second marks, and my example does not disappoint me.

So in the world of normal people there’s nothing to complain about, but eventually I had to take a loupe out for some unreasonably close inspection. The tiny print of the city codes is amazingly precise. The indices are clean and perfectly aligned. The dial surface itself is not particularly exciting but I like how the Oceanus logo and other print seem to float in full sun, since they’re printed on the surface of the fairly thick dial substrate and cast shadows on the solar cells deeper down.

The hands are just slightly beveled, with central trenches filled with lume. They look good from above, with a precise mirror polish, but their side edges are rough-looking from some angles under the loupe.

The hands look good from above, but if you get down low some rough finishing is visible.

The most disappointing element by far is the date window, which is roughly punched through the thick translucent dial. There’s a blue frame stuck around the hole in an apparent effort to conceal this rude finishing: at least it’s centered, but since the frame is a bit bigger than the hole, the sloppy edge remains visible. It would probably have been better to overlap the hole edge with the frame, but maybe that would have made positioning tricky or required an overly-thick frame.

Finishing on the date window doesn’t hold up to the generally high standards of the watch.

On the plus side, the window is well-placed, substituting for a 3 o’clock index, and the date display itself is well-proportioned relative to the rest of the dial.

Accuracy

People don’t talk much about quartz accuracy, I suppose because the assumption is that it’s always good enough. Casio rates the S100 for +/-15 seconds per month, which is fairly standard and at the same time as good it gets with a conventional quartz movement. If you go to thermocompensated quartz designs you can do +/-10 second a year or better, but the market is surprisingly (to me, anyway) disinterested in this. Quartz Grand Seikos just happen to be super-accurate in their general pursuit of perfection. When it comes to watches marketed explicitly on accuracy, you have your Certinas, that one Longines and the insane Citizen 0100 line. There are a smattering of models from other brands that use high-accuracy ETA Precidrive movements, but good luck ferreting them out. True high accuracy quartz watches are a tiny sliver of the quartz pie.

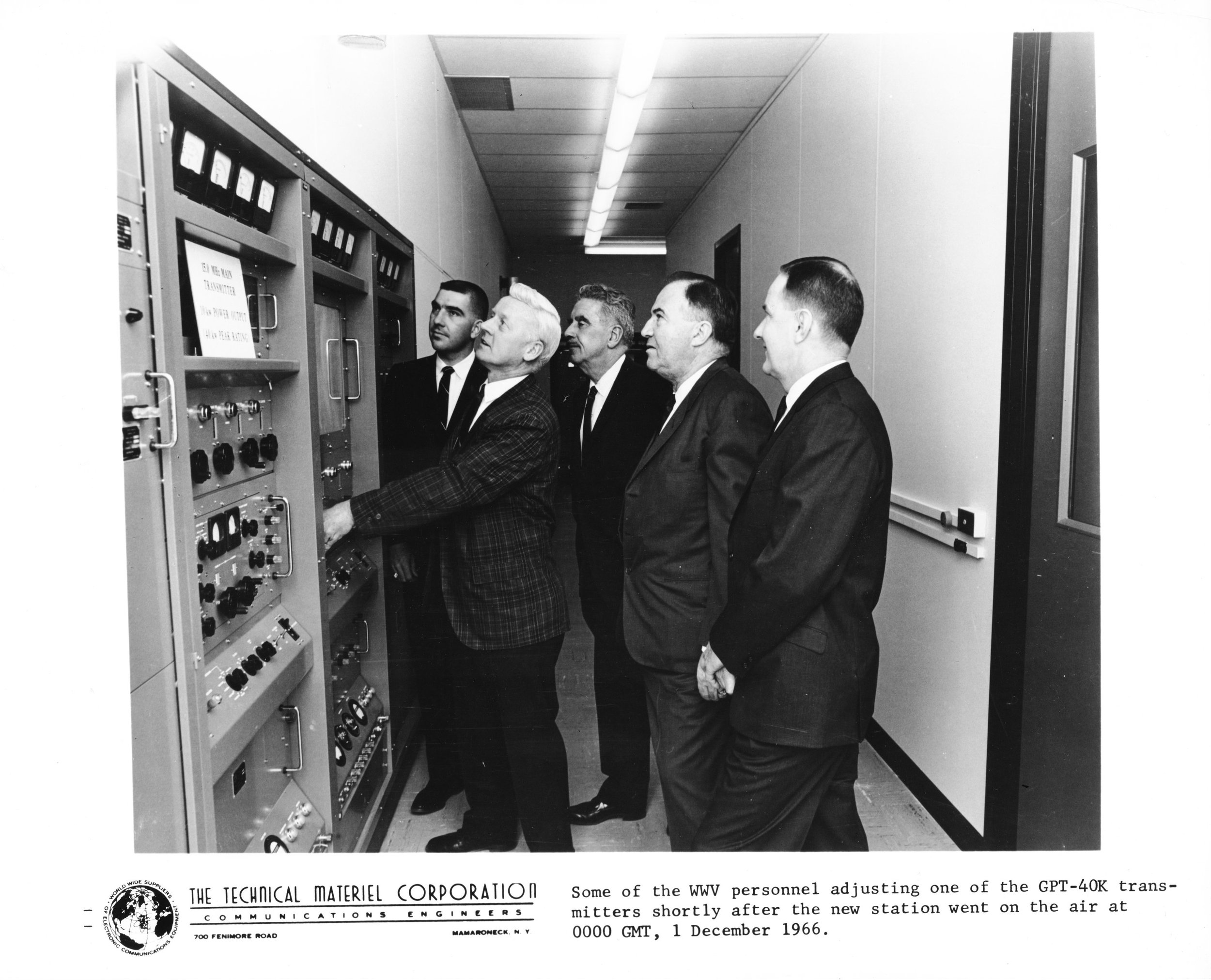

Of course the whole point of the radio-synchronized S100 is that even at the edge of its pedestrian accuracy spec, it should never be more than a second off if you’re in range of one of the six time transmitters it can pick up. Each transmitter is linked to a member of the loose network of atomic clocks that defines precise time for all of humanity. Starting around midnight, the S100, like any of Casio’s 6-Band Waveceptor models (there are many), will listen for a transmitter that’s relevant for its current timezone. At midnight, the sun is on the opposite side of the planet, and the deafening roar of its radiation crashing against the ionosphere is as faint as it will get. This makes it easier for the watch to hear the distant low frequency time signal as it flows across the ground, bending over mountain tops. The watch stills its second hand, quieting any interference the tiny motor might generate. The time signal is simply coded, amplitude cranking up and down to send one bit per second, with the whole time and date relayed over the course of a minute. There’s a lot of redundancy built in so the watch can piece together the time over several minutes if reception is choppy. And so once a day the watch is almost perfectly synced to time on Earth.

You can’t take a picture of accuracy, but I’ll bet these guys knew what time it was.

Some watch people think this is cheating, but I find beauty in the process. Frequent synchronising of timepieces was once part and parcel of owning them — the bonging of tower bells, the BBC’s time pips. Dava Sobel’s stone-cold classic “Longitude” describes (among many other things) the cottage industry that once existed around relaying the time from London’s Greenwich Observatory, with individual time sellers synching their chronometer at the Observatory and then carrying the time to their customers.

Anyway, in my casual testing the radio synch technology worked well: in Los Angeles the S100 grabs the signal from the thunderous WWVB in Fort Collins without much effort, and in Paris it can hear the much closer DCF77 signal from Mainflingen nearly anywhere in my apartment. I’ll hazard that if you’re reading this and have an S100, it will sync in most of the places in the northern hemisphere that you find yourself.

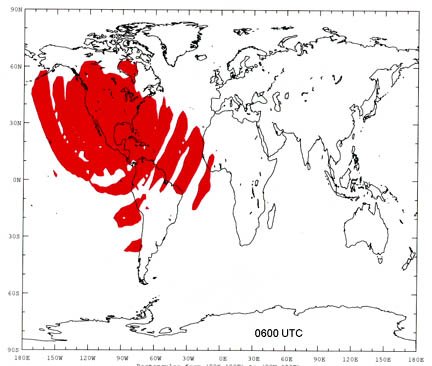

This map of WWVB’s maximal coverage (0600 UTC is midnight in Fort Collins) is courtesy of the NIST, the US governmental agency that operates the station. We see WWVB’s signal flashing out in the night, blanketing North America, washing across the Atlantic and Pacific, whispering the time on beaches in Libera, Sierra Leon, Ginea-Bissau, Suriname, Guyana, Peru. NIST also tracks WWVB’s reception in three of the four US time zones and publishes updates every ten minutes here.

In researching this review I came across a PDF scan of a 50-page booklet titled “WWVB Radio Controlled Clocks: Recommended Practices for Manufacturers and Consumers (2009 Edition)” published by the NIST, which I found fascinating despite (or because of) its dry, earnest tone. A representative quote: “When consumers check the accuracy of an analog RCC [Radio Controlled Clock, a term NIST advocates over ‘atomic clock’ unless 'there is actually an atomic oscillator in the RCC’], they need to be sure they are looking straight at the clock face and not viewing it from an angle. Consumers who view the clock from an angle might think it is off by a few seconds even if it is not. This is similar to trying to read the speedometer from the passenger seat of a car and thinking the speed is faster or slower than it actually is.” Clearly the author has some personal experience with an anxious parent or spouse in the passenger seat.

OK, my NIST digression has exceeded the capacity of an image caption. Recommended Practices also turned me on to a phone number, +1 303-499-7111, that allegedly plays “audio time signals.” When I called it I was connected to a strange piece of outsider art, a sound installation with a hypnotic beat that not only delivers the time in a cool old-timey instructional video accent but also reports the “space weather” in a robot lady voice. I recorded it for you:

But back to the watch: how does the S100 do without help? I turned the automatic radio sync off and tracked the unassisted watch over the course of three weeks. The S100 slowly drifted to -1 seconds, briefly hit -2, and then came back down to -1, then finished at -2. This was with the watch on my wrist for around 22 hours a day, which probably helped keep the temperature steady, but I was still impressed. Then I tracked it for another month and change, on and off the wrist, and it hovered around -2 seconds the whole time. Finally, three months after I started keeping track, it was at -5 seconds.

Now, I know what you’re wondering: what if I want to do some celestial navigation? If I was at sea without a GPS receiver could I determine my position with my S100? It takes about three weeks to sail across the Atlantic with a little luck, and in my unscientific test above, the S100’s unassisted quartz movement beat the first marine chronometers developed by John Harrison to solve the longitude problem in the 1700s (again, Sobel). If it was good enough for King George III, it’s good enough for me. But the S100 could probably even go a little better, since the radio time signals carry over water, sometimes for surprising distances. Sailing west from Europe via the southern passage takes you down from Portugal to the Canaries first, so you’d probably be out of range of the more-northern DCF77 pretty quickly (though maybe with a range extender you could draw things out). Soon, though, you’d begin to catch WWVB; that 70 kilowatt signal from Fort Collins covers impressively broad swathes of the Atlantic. Going west to east, you’d get WWVB for a while out of Bermuda, but you’d lose it deeper into the north passage and be in the dark for a couple of weeks before DCF77 came back around on final approach to Portugal. But if my experience is any indication (and of course it isn’t really — this is serious YMMV territory), you could crisscross the Atlantic form Europe to North America and back and never be more more than two seconds off UTC. So if I watch a few more YouTube videos, and get a sextant, a current edition of the Nautical Almanac, a map, a boat, and also learn to sail, I’m all set.

Verdict

I like the S100. I like its unassuming technical polish, its careful construction (with only a couple of dial elements falling short), its casual competence. I like that it’s out of step with the homage-obsession of the moment and that it’s kind of ugly until you look at it for a while. I like that its manufacture is impressively vertical but nobody gets precious about it because it’s a Casio. I like that no one will want to steal it because it’s a Casio. I like that it’s effortlessly accurate. I like that it listens quietly in the night.

Addendum: DXing in Oz

Recently (about a year after I first posted this review) I found myself on the east cost of Australia wearing my S100. My limited experience of Australia suggests that it is full of natural wonders, and trucks with snorkel attachments that let the engine breath when most of the vehicle is submerged, and generally well thought-out infrastructure. But despite having phone booths that make calls for nothing, surgically clean public toilets, free gas grills in the parks and a functional public health care system, they turned off their time transmitter at the end of 2002. Nobody's perfect.

Upon deplaning you can still set your time zone on the S100 (SYDney, in my case) and the watch appropriately adjusts relative to the previously set zone, but this pauses radio syncing until you come back to civilization.

However, I'd seen anecdotal reports that radio-synced watches in Australia can sometimes receive the signal from Japan's JJY. Curious, I set my watch to Japan's time zone (TokYO) and left it on a north-facing windowsill of my Airbnb in the small beach town of Marcoola, about an hour north of Brisbane. In the morning I was delighted to see that it had successfully received the time overnight. Probably from the Haganeyama transmitter in Saga, but maybe from the Otakadoyayama transmitter in Fukushima -- the watch checks both, which provide overlapping coverage on 40 and 60 KHz. Then it was just two clicks of the crown back to SYD, and I was all set.

For those who are, as was I, a little fuzzy on the geography of this part of the planet, let me put this feat in perspective. JJY is designed to reach out about a thousand kilometers from its two transmitters, handily covering the home islands. There's no need to go father. Japan isn't in the business of giving anything to China, and they have their own transmitter anyway (I tried to pick that one up, too, but no dice). But the crow-flies distance from Saga to Marcoola is more than 7,000 kilometers. Granted, a lot of that is over open water, but still. Color me impressed.

JJY is of course the S100's mother station. It would have been the first signal the watch received when it woke up in the Yamagata factory. I wonder if hearing it again felt like coming home.