I went to see The Making of Exiles at the Pompidou Center the other day because I heard Koudelka used a Leica. I’m kidding. I went because it was free and the internet has conditioned me to not pay for things. I jest. I went because Koudelka is, if not a god, a kind of John the Baptist of photography, or at least a Caine of Kung-Fu of photography. And like I said, it was free.

Koudelka recently gave the museum a bunch of prints from which this show is drawn. They’re from his Exiles work, which I’d heard of but never seen seriously (I was more familiar with his photos of gypsies [or Roma, or Travelers, or what have you], which, I learned, he shot with an Exacta and a 25mm Flektogon, which must have seemed insanely wide at the time). I also learned that Koudelka is still alive. Not that I’d heard he wasn’t, but I just kind of assumed, you know. Not only is he alive, but he’s active.

He has always been active. I knew, vaguely, something about Koudelka’s personal story, but it seems my mind refused to retain the full incredibleness of it. Between the show notes and some heavy Koudelka creeping online, I am now reacquainted. You may know that he is a Magnum photographer, a friend of the great (late, this I knew) Henri Cartier-Bresson (in fact, I read that HCB got him those Leicas I mentioned). Quite firmly ensconced in the firmament. But so, Koudelka had (has?) this magnificent process. He spent his arguably most fruitful years, or at least the years he’s most famous for, wandering the earth (the western European part of it, anyway). Like Caine. But I mean, really a lot more like Caine than other photographers who get around. Koudelka wandered, with just his cameras and film and a sleeping bag and his ideas. He owned nothing unrelated to creation or survival, had no fixed address. He would photograph during the spring and summer, sleeping where he was when the day ended, outside or on the floor of an obliging friend or stranger, which this show gets into in some novel detail. In the winter he fell back to London or Paris (crashing in the Magnum offices at times) to develop and edit his work. He did this for years, decades. He never married, but has three children with three women in three countries. And claims to abhor spending more than three months in one place. That is a lot of threes. I have seen nothing to suggest that this breathless account is untrue, or even a stretching of truth.

And did I mention that his first and last piece of photojournalism was the single-handed documenting-for-western-eyes of the brutal Soviet-led invasion of Prague in 1968, which won him (anonymously, so the Reds wouldn’t thank him with free and permanent underground housing) the Capa Gold Metal for excellence in photojournalism? Not bad for a guy who up till that point was fixing airplanes and taking pictures of theatre productions and rootless Roma, who were no doubt rough around the edges but rarely shot at anyone, unlike the Warsaw Pact troops, who managed to kill over a hundred of Koudelka’s countrymen while liberating them from the grips of imperialist infiltrators. Well, consider it mentioned.

So, the show. Obviously, it’s good. Duh. If you don’t find something that engages you there, we have nothing else to say to each other. But this is supposed to be a review, so let’s review.

There is, to start, one of Kudelka’s most iconic photos, the dog, the black dog, that was on the cover of Exiles. They used it for the show’s poster, but there’s a real print inside.

What is it about this image? It’s a dog picture. A dog in a park. It does not start well. But then, it is amazing, and it’s quite a treat to see a real print of it. I think it works because of the way Koudelka pushes the abstracting power of black and white film. If it were printed to show the documentary truth, it would not be as interesting. But the unrelieved blackness of the dog makes its outline the primary element of the image, the freakish jowls, the knobby, demonic tail. There is a strangeness that would not have been apparent in the moment to someone without vision. I have been there, the Parc de Sceaux, dozens of times, in the snow even, and of course I never saw anything like this, because you have to be someone like Josef Koudelka to see it in the world. Then he shows us what he saw, and we understand that one cold day the dog comes for all of us. In the show print, for the first time I noticed a human figure in the distance. With the blank snow obliterating the separation of foreground and background and little else to guide our understanding of perspective in the image, the person makes the dog feel enormous.

Then there’s something like this:

The photographer always inserts himself in the photograph, especially when shooting other people's highly reflective photographs.

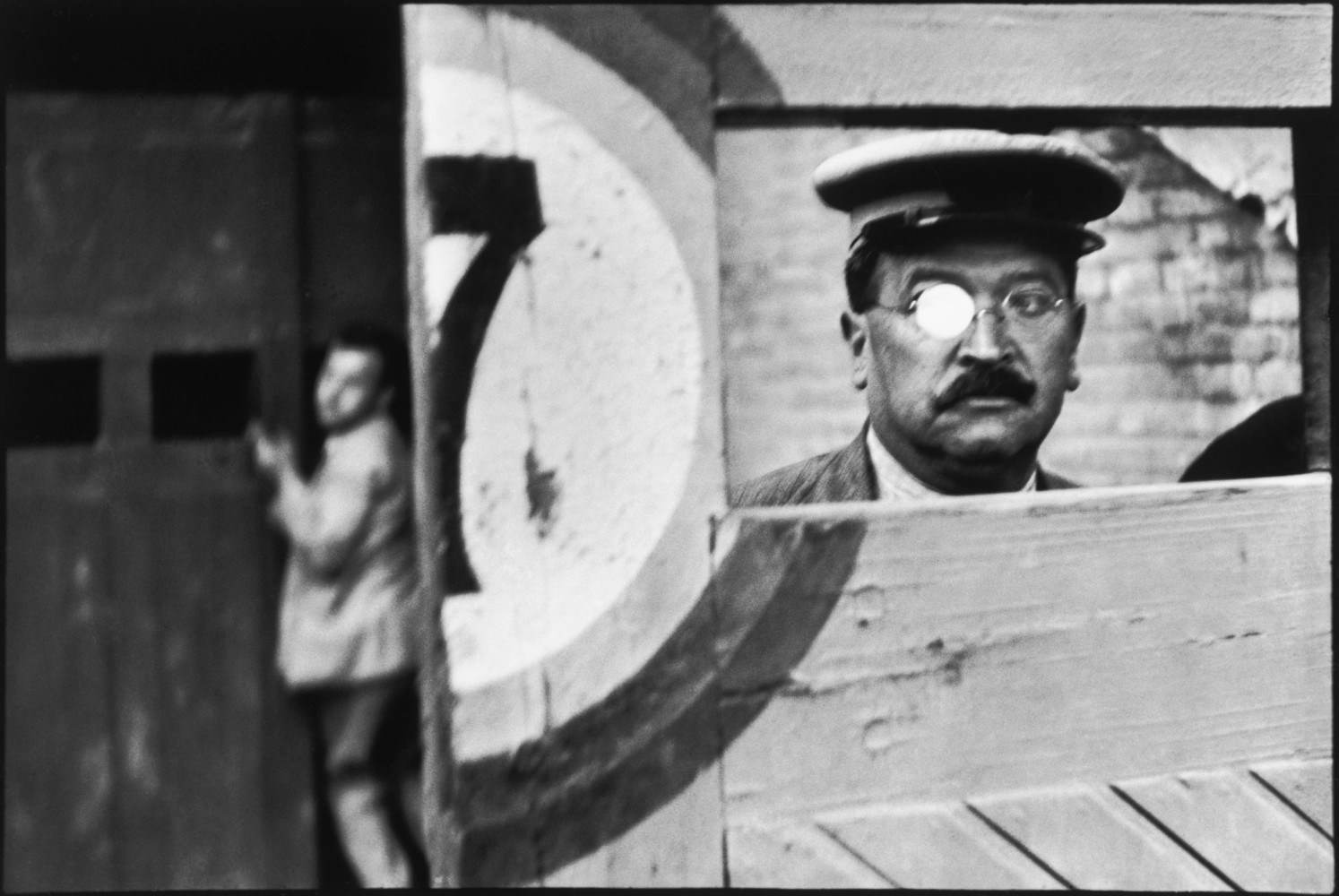

I don’t think of Koudelka as being (even before he got into panoramic landscapes) really a “street photographer” – that’s much too tight a box to squeeze him into. But he did manage some blistering street photography all the same. What’s going on in this shot? What’s the point? I sure as hell don’t know. Is that old man creepy or kind? What’s the deal with that kid? Koudelka isn’t going to tell us. He just drops the moment on us. The rest is in our hands. Here we have some desperation, some hope, some every-day-getting-along. Look at that lady’s stockings: they speak whole soliloquies of getting along. The subject is something, but compositionally we’re also in fresh territory, with the halving of the man, the division of the whole image.

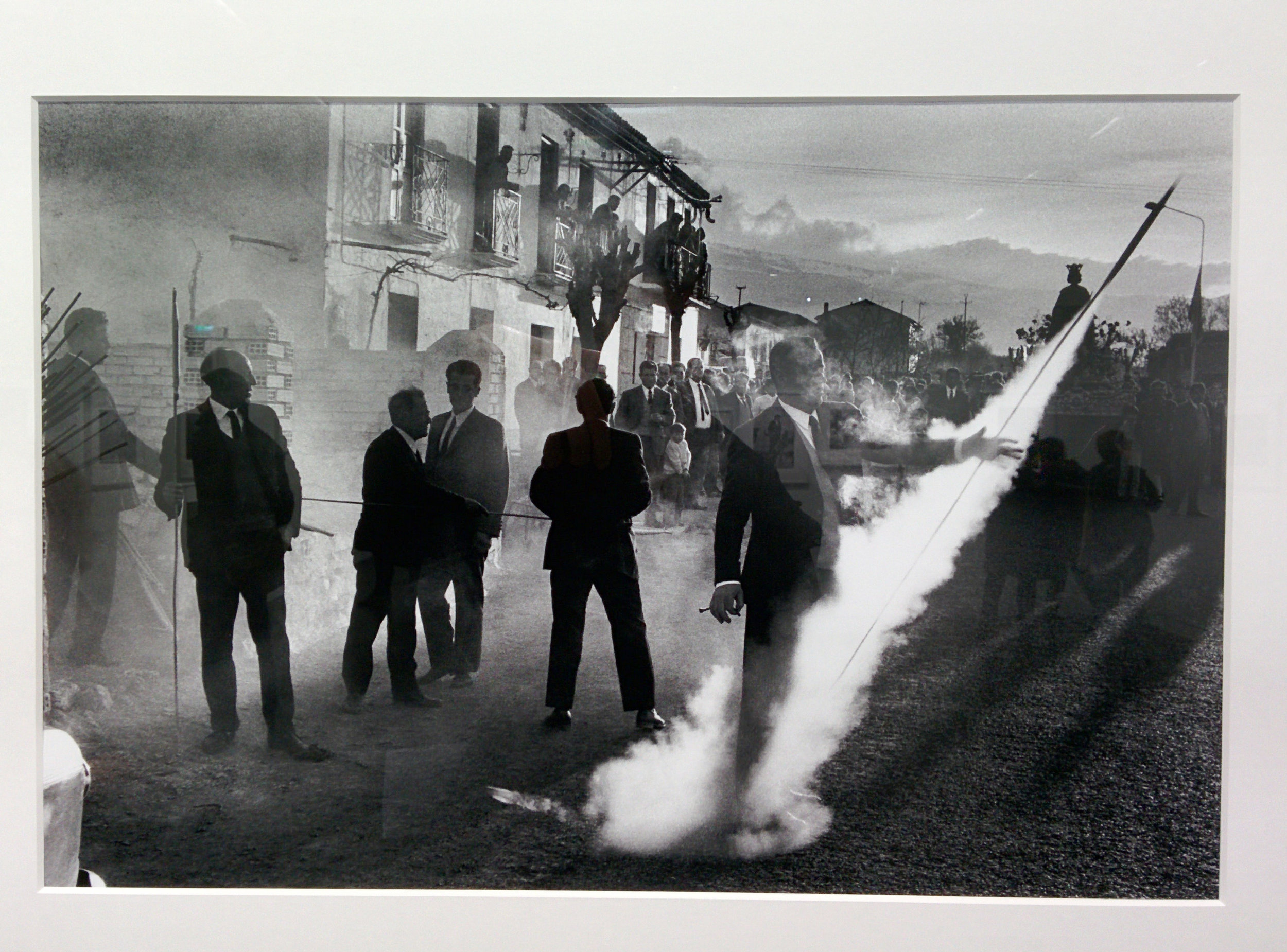

How about this?

The black silhouettes again, the incredible light on the rocket plume, the timing, the way the smoke doesn’t just obscure the man but calls into question his very form, I mean, holy shit. This moment did not look like this, but it was this, could be shown to be this.

Not everything got me this excited. There are several images of rough cloth, studies of texture or comments on the fabric of lives, I don’t know.

Then there was this grouping:

The top photo, gulls presumably following a boat, doesn’t seem far off from plenty of stuff on Flickr. But considered as part of the tryptic it says more, a progression along the track of animals’ relationship with man, from relative freedom through pathetic captivity to exploited death. That crow is quite something, though I wonder if back then people tied up dead crows (a scarecrow of the most pointed variety, I assume) all the time, and the subject’s impact is a trick of anachronism. The clever corvid was not always as appreciated as today.

There are two series of photos that are explicitly marked as being never-before-seen: one, a collection of makeshift outdoor sleeping places presumably used by the man himself, and the other, timed selfies of Koudelka pretending to snooze. The leaflet describes these as not merely unpublished but “secret,” and I can almost believe it. But they don’t come completely out of left field: there is, for example, a picture in the original collection of Koudelka’s legs stretched out before him that prefigures a million Instagrams. And the apparently famous arm-with-watch in Prague (which I couldn’t recall ever seeing, to the utter astonishment of the friend I went to the show with). But their inclusion is certainly a departure in tone and subject, and arguably puts more emphasis on the artist’s nomadic, ascetic lifestyle in a new way, in a way he never did back in the day.

Let’s just stop and marvel at this, here in 2017. People now can’t resist talking up the whole nomadic monk thing because it’s just awesome, but the really amazing thing is Koudelka just did it, near as I can tell, not to make a point about materialism or show girls how woke he was, but because he wanted to make certain kinds of photos so he got rid of everything that wasn’t about making certain kinds of photos. He wasn’t selling a book about simplifying your life, and you don’t need to know anything about the guy’s process to see what’s good about his work. His lifestyle makes the work possible, but it isn’t part of the work. A young photographer showing the same disinterest today is nigh unimaginable.

But, those beds and selfies. This is a rare treat, a lifting of the curtain, and interestingly shows that Koudelka himself was, on some level, interested in his process/life-style. Did he just want to preserve those one-night-stands for his own recollection? Did he like the visual of those empty beds? Did he wonder what he looked like, sleeping there with no one to see him but the stars and night-creatures? Did he want proof that he wasn’t sneaking into a hostel every chance he got? Characteristically, he doesn’t drop any metatextual hints in the show apart from a quote about how he managed to sleep anywhere.

So, see the show. Ponder the man’s vision, and his meanderings, and his refreshing non-performativeness.

[A side note: last year I saw another free show at the Pomp, Louis Stettner. Great show. “Free” is not the word that comes to mind when I think of this museum, but there’s a space downstairs called the “Galerie des Photographies” and as far I can tell, it’s always free. They’ve been putting up shows there since at least 2014, but I only just heard of it recently, at least in part because the events there don’t show up on the list of expositions on the museum website. They are listed, separately, but are incredibly hard to find from within the site – Google does a better job. In fact, you could easily visit the Pompidou Center in person and miss these things. To make sure you don’t, go straight to the back wall from the entrance and do a 180 to take the wide stairs down into the bowels of this boweliest of buildings.]

And a closing note: I’ve come across a number of mentions of notebooks that Koudelka kept during his wanderings, but have never seen anything purportedly excerpted from them. I imagine he still has them, they’re probably in Czech, and probably no one knows what’s in them. But if English pearls have been extracted from these presumable oysters, I’d love to know about it.

Finally, let’s watch a video. This by all rights should be cultural ephemera, but it has been amber trapped by the INA, an utterly French sounding-institution dedicated to “the preservation and promotion of our audio-visual heritage,” which I’d never heard of but is clearly wonderful. This was French public television just before the wall came down. Look at that lady’s outfit. I was not only alive in 1988, but sentient. I lived this (albeit elsewhere) yet it looks like a period piece, or a punchline. You can skip to 00:15 for a deliciously awkward long pause as they cue up the next segment, and then marvel at the glimpse of Koudelka’s gloriously trashed, rough-sleeping Leica hanging around his neck, set to an ominous drone that calls Werner Hertzog to mind. Then you can stop it and go on with your life as if every moment didn’t contain miracles.